Why KRAS Mutations Make EGFR Drugs Ineffective: A Precision Oncology Lesson

In my previous post about my family’s cancer journey (with personalized medicine), I touched on how molecular diagnostics are reshaping cancer treatment. One of the clearest examples of this is the interaction between EGFR and KRAS in colorectal and lung cancers. Understanding this pathway helps explain why certain therapies fail—and why is essential.

Disclaimer: Much of the content here is the integration of my own research of the current literature with assistance with AI. Although I have degrees in chemistry and have performed research in biophysics, I am not an expert on cancer biology. In the supplemental I investigate the mechanisms from a biophysics standpoint in case you’re interested. I’m working to confirm all of the information and references are correct.

The Role of EGFR in Normal Cells

EGFR (Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor) is a receptor tyrosine kinase that functions like an antenna on the cell surface. It receives external growth signals and transmits them into the cell to drive division and survival.

The signaling process works like this:

- Ligand Binding: Growth factors like EGF bind to EGFR.

- Dimerization: Two EGFR molecules pair up on the cell surface.

- Activation: This activates their internal kinase domains.

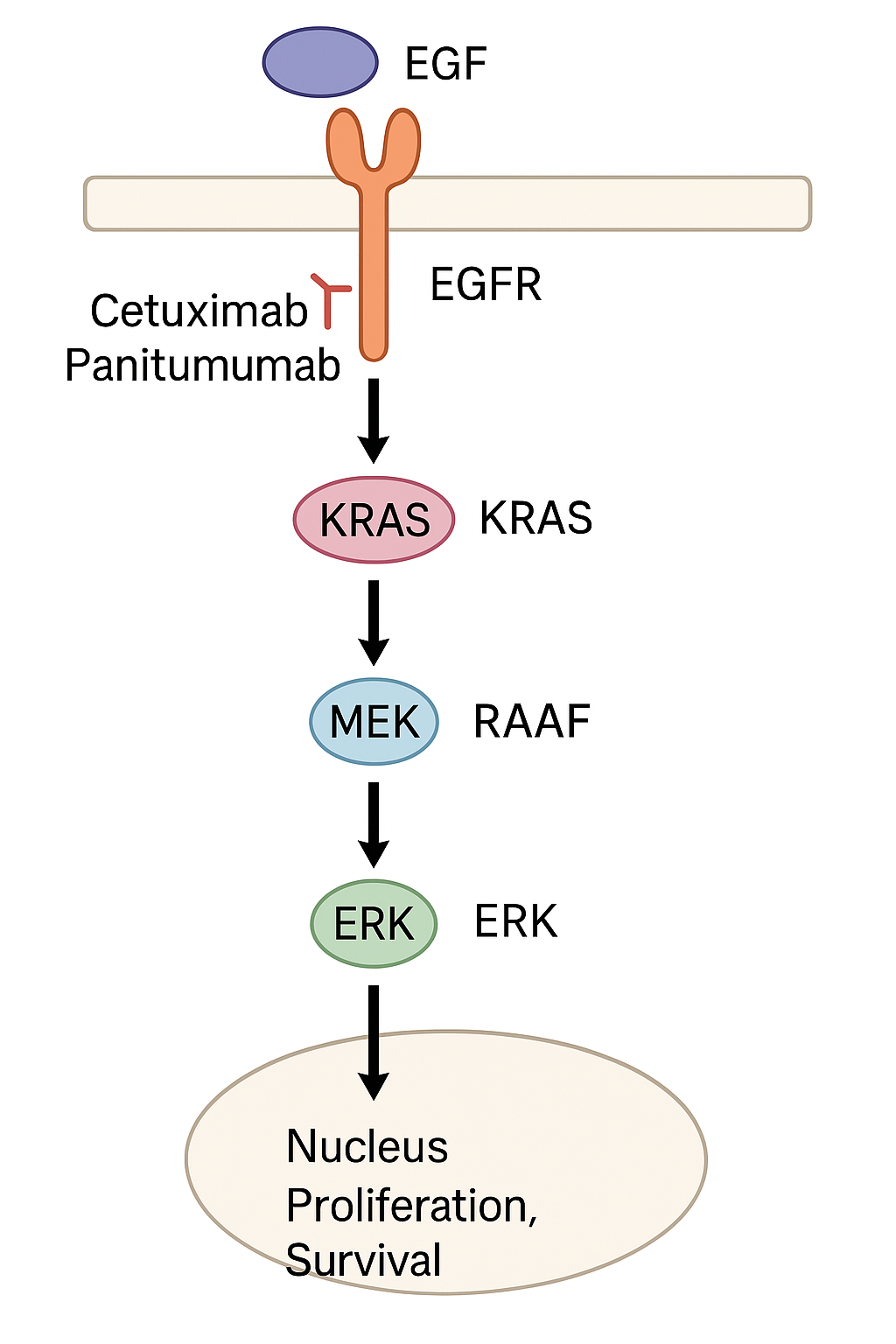

- Downstream Signaling: A phosphorylation cascade begins—EGFR activates KRAS, which activates RAF, then MEK, then ERK—ultimately triggering gene transcription and cell proliferation.

This pathway is tightly regulated in normal cells.

How EGFR Drives Cancer—and How We Try to Block It

In some cancers, EGFR is overexpressed or mutated, leading to continuous growth signals. That’s where EGFR inhibitors come in.

There are two major classes:

- Monoclonal antibodies (e.g., cetuximab, panitumumab) block the extracellular domain of EGFR to prevent ligand binding and dimerization.

- Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) (e.g., gefitinib, erlotinib) block the intracellular kinase domain of EGFR to stop phosphorylation and signaling.

These therapies can work well—but only if the cancer relies on EGFR for growth.

Why EGFR Drugs Don’t Work in KRAS-Mutant Tumors

KRAS is a downstream signaling molecule. In its normal form, it acts like a switch that turns on when EGFR sends a signal. But in cancers with KRAS mutations, the switch is stuck in the ON position—it signals constantly, regardless of what’s happening upstream.

This means:

- Blocking EGFR doesn’t stop the growth signal.

- KRAS keeps activating RAF → MEK → ERK.

- EGFR inhibitors become clinically ineffective.

This is why KRAS mutation testing is mandatory before giving EGFR-targeted drugs in colorectal and lung cancer.

📊 Summary Table

| Tumor Profile | EGFR Active | KRAS Mutated | EGFR Inhibitor Effective? |

|---|---|---|---|

| EGFR Overexpression | Yes | No | ✅ Yes |

| EGFR Activating Mutation | Yes | No | ✅ Yes |

| KRAS Mutation (e.g. G12D) | Irrelevant | Yes | ❌ No |

Visualizing the Pathway

This diagram illustrates the signaling cascade from EGFR → KRAS → RAF → MEK → ERK → cell proliferation. It also shows where drugs like cetuximab intervene—and why they don’t work when KRAS is mutated.

Not All KRAS Mutations Are the Same

The most common mutations in KRAS occur at codon 12, but others happen at codon 13 or 61. These point mutations subtly change the KRAS protein structure, altering its biochemistry and druggability.

| Mutation | Amino Acid Change | Prevalence in KRAS Mutations | Common Cancer Types |

|---|---|---|---|

| G12D | Gly → Asp | ~30% | Colorectal, Pancreatic |

| G12V | Gly → Val | ~23% | Pancreatic, Lung |

| G12C | Gly → Cys | ~13% | Lung (NSCLC), Colorectal |

| G12A | Gly → Ala | ~6% | Colorectal |

| G12S | Gly → Ser | ~4% | Pancreatic, Colorectal |

| G13D | Gly → Asp (codon 13) | ~7% | Colorectal |

Source: Prior et al., Cancer Research, 2012; COSMIC Database

How the Shokat Lab Cracked KRAS G12C

For decades, KRAS was considered “undruggable”—its surface was smooth and lacked any obvious drug-binding pockets. But that changed with the work of Kevan Shokat’s lab at UCSF.

They discovered a unique vulnerability in the G12C mutation: the cysteine substitution allowed covalent binding of a drug molecule to an allosteric pocket when KRAS is in the GDP-bound (inactive) state.

This led to the development of:

- AMG 510 (sotorasib) – FDA-approved for KRAS G12C NSCLC

- MRTX849 (adagrasib) – Also showing efficacy in lung and colorectal cancers

These drugs selectively bind to KRAS G12C and shut off its activity, marking the first real success in directly drugging KRAS.

Cited: Ostrem et al., Nature, 2013 (Shokat Lab)

Why G12C Drugs Don’t Work for G12D, G12V, and Others

Unfortunately, other common KRAS mutations like G12D or G12V do not introduce a cysteine at position 12. Without the reactive sulfur group, covalent binding is impossible.

New strategies are being explored:

- Non-covalent inhibitors (e.g., MRTX1133 for G12D)

- KRAS degraders targeting the whole protein for destruction

- Upstream/downstream modulators (SHP2, SOS1, ERK inhibitors)

- Neoantigen vaccines and T-cell therapies tailored to KRAS mutations

We’re now moving from a world of “undruggable KRAS” to “selectively druggable KRAS.”

Clinical Data and Trial Outcomes

-

KRAS Inhibitors in Colorectal Cancer: Recent studies have shown that combining KRAS G12C inhibitors like sotorasib with EGFR inhibitors can lead to improved progression-free survival in patients with colorectal cancer. For example, the combination of adagrasib with cetuximab has demonstrated response rates around 46% in phase 2 trials, indicating enhanced efficacy over monotherapy.

-

Resistance Mechanisms: Understanding how tumors develop resistance to EGFR inhibitors despite the presence of KRAS mutations is crucial. Mechanisms such as the reactivation of the MAPK pathway or alterations in downstream signaling components can contribute to this resistance, highlighting the need for combination therapies and novel agents.

Final Thoughts

KRAS mutations are among the most frequent oncogenic drivers in cancer—and they’re a major reason some targeted therapies fail. But with better diagnostics and smarter drug design, we’re finally breaking through.

This is precision medicine in action. Knowing whether a tumor has a KRAS G12D, G12C, or no mutation at all is not an academic detail—it’s the difference between wasted time and effective care.

References

- Prior, I. A., et al. (2012). A comprehensive survey of Ras mutations in cancer. Cancer Research, 72(10), 2457–2467. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2612

- Ostrem, J. M., et al. (2013). K-Ras(G12C) inhibitors allosterically control GTP affinity and effector interactions. Nature, 503(7477), 548–551.

- Canon, J., et al. (2019). The clinical KRAS(G12C) inhibitor AMG 510 drives anti-tumour immunity. Nature, 575, 217–223.

- Cox, A. D., et al. (2014). Drugging the undruggable RAS: Mission possible? Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 13, 828–851.

- COSMIC: Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer. https://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cosmic

Please see this follow-up article KRAS-Mutated Colorectal Cancer: New Treatments, Realities, and What to Expect where I explore the landscape of next-generation KRAS inhibitors and how biotech is tackling the challenge of G12D, G12V, and other difficult mutations.

Supplemental Part 1: Understanding the Unique Mechanism of KRAS G12C Inhibitors

The KRAS G12C mutation, which substitutes glycine for cysteine at position 12, creates a critical dysfunction in the regulation of KRAS activity. Normally, KRAS switches between an active (GTP-bound) and inactive (GDP-bound) state, regulated by GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs). GAPs accelerate the hydrolysis of GTP to GDP, thus turning KRAS “off.” However, the G12C mutation disrupts GAP binding, leaving KRAS constitutively active and driving uncontrolled cell proliferation.

Despite this mutation preventing proper GTP hydrolysis, it also introduces a unique therapeutic opportunity. KRAS G12C retains a slow, intrinsic rate of GTP hydrolysis, meaning that over time, a small portion of the mutant protein will revert to the inactive, GDP-bound state.

This brief inactive state opens the door for targeted therapy:

- Structural Vulnerability: The G12C mutation creates a unique, druggable pocket in the GDP-bound conformation that is not present in the wild-type protein or the GTP-bound form.

- Drug Action: Inhibitors like sotorasib and adagrasib covalently and irreversibly bind to the cysteine residue when KRAS is in this inactive state, locking it in place and preventing reactivation.

- Effect Over Time: As the active KRAS slowly cycles to its inactive form, more molecules become drug-bound and locked down, depleting the pool of active KRAS and shutting down downstream oncogenic signaling.

This approach cleverly does not attempt to restore hydrolysis, but instead exploits a fleeting moment of vulnerability created by the mutation. It’s like placing a padlock on a broken light switch that occasionally flips off by chance, ensuring it stays off permanently.

Why KRAS G12C is Unique — And What That Means for G12S and Other Mutations

While G12C inhibitors represent a milestone, they highlight how chemically tractable mutations are the exception, not the rule. The key enabler for G12C-targeting drugs is the reactive thiol group (-SH) of cysteine, which allows covalent binding.

Other common mutations — like G12S (serine), G12D (aspartic acid), and G12V (valine) — lack such reactive groups, making the same “covalent-lock” strategy impractical. Serine, for instance, has a hydroxyl group (-OH) that is much less chemically reactive than cysteine’s thiol.

Here’s how researchers are approaching G12S and other KRAS mutants:

-

Non-Covalent Inhibitors of the Inactive State

Drugs may be designed to bind non-covalently to the GDP-bound form of G12S, stabilizing its inactive state. This is extremely challenging due to the high intracellular concentration of GTP and the need for specificity to mutated KRAS. -

Allele-Specific Inhibition

An emerging approach involves designing molecules that selectively recognize structural differences in the G12S mutant protein. While this doesn’t rely on a reactive group, it requires precise molecular engineering to differentiate the mutant from wild-type KRAS. - Indirect Inhibition

Rather than targeting KRAS directly:- Downstream inhibitors (e.g., MEK, ERK inhibitors) can block the signaling pathways KRAS activates.

- Upstream inhibitors (e.g., SOS1 or SHP2 inhibitors) can prevent KRAS from becoming activated in the first place.

However, these strategies may be limited by redundancy in signaling pathways and toxicity concerns.

- Innovative Modalities

New tools are in early development:- PROTACs: Small molecules that tag mutant KRAS for degradation.

- Gene-editing tools: Such as CRISPR/Cas9 aimed at correcting or removing the mutant allele.

- mRNA and antisense therapies: To reduce KRAS mutant protein expression.

Why It Matters: Personalization Beyond G12C

These nuances underscore a critical point in precision oncology: not all KRAS mutations are equal. While G12C accounts for a significant portion of KRAS-driven lung cancers, mutations like G12D, G12V, and G12S dominate in colon, pancreatic, and other cancers — and are still in urgent need of targeted options.

The development of G12C inhibitors was a breakthrough, but their success raises the bar for addressing more complex and less chemically tractable variants of KRAS. As with many cancers, personalized treatment hinges on deeply understanding the exact mutation, its biochemical behavior, and how to exploit its unique vulnerabilities — or work around its resistance mechanisms.

Supplemental part 2: Molecular Biophysics and Therapeutic Targeting of KRAS Mutations

This supplement expands upon the concepts discussed in the main article, offering a detailed structural and mechanistic view of KRAS as a molecular switch — and how the G12C mutation both breaks and reveals new therapeutic vulnerabilities.

KRAS GTPase: A Masterclass in Allostery and Conformational Switching

KRAS is a small GTPase that acts as a molecular toggle, cycling between an “on” (GTP-bound) and “off” (GDP-bound) state. This cycle is tightly regulated by upstream signals and accessory proteins.

The Normal “On-Off” Cycle

KRAS function hinges on two key conformational elements:

- Switch I (aa ~25–40): A flexible loop that changes structure based on the bound nucleotide.

- Switch II (aa ~60–76): Another mobile region that complements Switch I.

In the GTP-bound state (active):

- Switch regions adopt a rigid, exposed conformation.

- This allows binding to downstream effectors such as RAF, initiating the RAF-MEK-ERK pathway.

- Membrane recruitment and effector activation drive cell proliferation and survival.

In the GDP-bound state (inactive):

- The switch loops collapse, hiding the effector-binding surface.

- GAP proteins accelerate GTP hydrolysis to GDP, turning the signal off.

(References: Vetter & Wittinghofer, Science, 2001; Stephen et al., Cell, 2014)

The Structural Consequence of G12C: From Oncogenesis to Opportunity

The G12C mutation replaces glycine with cysteine at a crucial location in the P-loop, a region that interacts with the phosphate groups of GTP.

Molecular Impact of G12C:

- Glycine’s small size allows GAP proteins to insert an “arginine finger” into the active site and catalyze hydrolysis.

- Cysteine is bulkier and sterically blocks GAP binding, impairing GTP hydrolysis.

- KRAS remains locked in the GTP-bound, active state, continuously recruiting RAF and propagating oncogenic signals.

- This drives unregulated cell division, independent of upstream control.

Yet a Window Opens…

Despite its constitutive activity, KRAS G12C retains some intrinsic GTPase activity. A fraction of KRAS eventually transitions to the GDP-bound state. This brief, rare conformation creates an exploitable therapeutic window.

Targeting KRAS G12C: A Biophysical Feat

Covalent inhibitors such as sotorasib (Lumakras) and adagrasib (Krazati) target a unique, cryptic pocket exposed only in the GDP-bound conformation of KRAS G12C.

Mechanism:

- The thiol group (-SH) of the mutant cysteine allows covalent drug binding.

- These inhibitors bind in an allosteric pocket under Switch II, locking KRAS in its inactive state.

- Over time, as more molecules cycle through GDP-bound form, they become irreversibly trapped by the drug, depleting active KRAS.

This is not a reactivation of hydrolysis, but a clever use of conformational dynamics:

“It’s like placing a padlock on a broken light switch that occasionally flips off by chance—ensuring it stays off permanently.”

(References: Ostrem et al., Nature, 2013; Canon et al., Nature, 2019)

Beyond G12C: Why Other KRAS Mutations Are Harder to Drug

G12C inhibitors are possible because cysteine is chemically reactive. But other common mutations — such as G12D, G12V, and G12S — lack this thiol handle, presenting major challenges.

Examples:

| Mutation | Side Chain | Reactivity | Drug Targeting Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|

| G12C | Cysteine | Thiol (-SH) | Covalent binding possible |

| G12D | Aspartic Acid | Carboxylate (-COO⁻) | Non-covalent only |

| G12V | Valine | Hydrophobic | No reactive group |

| G12S | Serine | Hydroxyl (-OH) | Weak nucleophile |

(References: Hallin et al., Cancer Discovery, 2020; Ryan et al., Nature Reviews Cancer, 2022)

Why It Matters: Personalized Therapy Depends on the Mutation

Understanding the exact KRAS mutation — not just the presence of “mutant KRAS” — is essential to determining treatment.

- G12C → Covalent inhibitors are FDA-approved.

- G12D/V/S → Still lack direct therapies.

- Colorectal and Pancreatic cancers → Often have non-G12C mutations, which remain resistant to targeted therapy.

The success of G12C inhibitors shows what’s possible when biophysics meets precision medicine. But it also underscores how much further we must go to reach the full spectrum of KRAS-driven cancers.